There are several reasons why I decided to write a blog sharing behind-the-scenes information on filming the short documentary "Through the Eyes of a Vulture." For one, the less than seven minute video doesn't tell the full story. We wanted it that way. We set out to produce a short, get-to-the-point film that helped depict the East African vulture crisis. Missing though is the journey. The days we spent tracking the large wildebeest herds, finding carcasses, and finally successfully capturing vultures. By using my journal notes and photos taken by people along the way, I will finally be able to tell the full story.

There are several reasons why I decided to write a blog sharing behind-the-scenes information on filming the short documentary "Through the Eyes of a Vulture." For one, the less than seven minute video doesn't tell the full story. We wanted it that way. We set out to produce a short, get-to-the-point film that helped depict the East African vulture crisis. Missing though is the journey. The days we spent tracking the large wildebeest herds, finding carcasses, and finally successfully capturing vultures. By using my journal notes and photos taken by people along the way, I will finally be able to tell the full story.

I flew back to Africa in late August/early September of 2012 to witness the Great Migration of the wildebeest and zebra. A lot of people have asked why it took nearly a year and a half to complete the documentary. There are various reasons why, but it mainly had to do with timing and my national media appearance schedule. A month after filming wrapped in Africa, I began making regular appearances on "The Today Show." (Talk about a dream come true!) Having to juggle those appearances and my tour schedule, it was difficult to find a set amount of time to work exclusively on the project. Not to mention my long-time editor is located out of state. Luckily we both found time and in the end it all worked out for the best!

As mentioned in the documentary, The Great Migration is the best time to capture vultures. So many animals lose their lives during this never-ending journey. Some are killed by large predators like lions and hyenas; although most actually succumb to pure exhaustion. Our job was to follow the herds. We would take note of their exact GPS location and return the next morning. Wherever the herds were, there was bound to be a causality during the night.

The next morning we would head out around 6 am to search the Mara Plains. We had to find our carcasses fast. The only good time to capture vultures is in the morning. Once the afternoon heat hits, its all over. The birds become stuffed and sluggish, preferring to roost or bask on termite mounds.

Some carcasses were just unusable. Munir actually remembered this particular zebra alive the week prior during a visit to the Mara with his family. It was wandering around alone in this particular area. It is unknown how the zebra actually died.

A perfect carcass is one that is fresh (usually the animal died the night prior) and open, exposing the soft tissue that allows the vultures to feed. Generally when we found our "perfect" carcass, the scavengers already beat us to it. This included the vultures and the Marabou Storks.

We would drive up and the birds would fly away...but never too far. We would set the traps and drive off. In minutes the birds would be back feasting on the carcass. All we would have to do is wait. As mentioned in the documentary, the Peregrine Fund does not allow the filming of their capturing techniques. This is for the sole purpose of protecting the vultures. Six out of the eight species of vultures found in Kenya are endangered or threatened. The last thing they need is people knowing how to catch one.

I would lying if I said we weren't under pressure trying to capture vultures. Dr. Henrik Rasmussen from Savannah Tracking was making the 6 1/2 hour journey from Nairobi to specifically put a GSM-GPS unit on a vulture for tracking purposes. We had to successfully capture a vulture. Munir told me we weren't stopping for anything. Sure enough as Murphy's Law would have it, we ran into elephants! These were the first wild elephants I'd seen since January. Apparently the elephants don't care much for the wildebeest herds; they avoid them at all costs. So wherever you find the herds you can assume the elephants will be at the opposite end of the park! We were lucky to find them. I have to also give Munir credit for breaking his rule to stop so I could film!

Murphy's Law worked its magic again! On our way to the southern end of the Masai Mara near Lookout Hill we came across a cheetah family! It was a mother with four cubs. We'd seen this family the day prior; although they were swarmed with tourists! This time around it was just us. I couldn't believe it. I will never forget Munir telling me the best wildlife sightings are the ones you just "stumble upon." He was right.

Special Note: The cheetah family was filmed and will be documented along with other African wildlife in the upcoming documentaries "This is Africa" due late spring. The documentaries will focus exclusively on the other animals we came upon during the time spent searching for vultures.

Minutes after our cheetah family encounter I spotted something jumping in the grass far off in the distance. I couldn't believe it! It was a serval with kittens! I never thought in my wildest dreams that I would ever see one of these small cats in the wild. Servals have excellent camouflage and generally hide in the long grass.

One of the biggest jokes on the trip was how bad my vision was. The "birds" or "carcasses" I had thought I'd seen usually turned out to be logs or rocks. You can imagine my excitement when I saw a large, dark blob in the grass. I had discovered a very fresh wildebeest carcass! At first we were hesitant to get out of the car. It was that fresh. After we checked the eyes to make sure the wildebeest was indeed dead, I was able to get an intro shot seen in the documentary. In the end we never even used this wildebeest to capture vultures. Willard had just died and his thick hide was impenetrable to both us and the vultures. Luckily a few hundred yards away we found another carcass that had been mutilated by hyenas. Chewed off feet and missing parts of the hide all give the indication this wildebeest was eaten by hyenas. Vultures were already feeding on the carcass. The setting was perfect. We set the traps and waited...

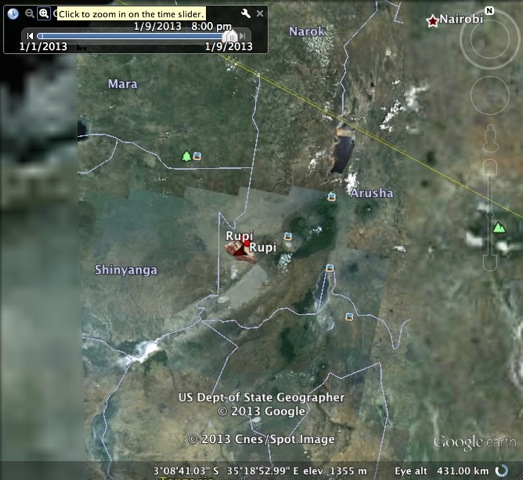

Success! We managed to capture three birds; one Rüppell's Vulture and two White-backed Vultures. We decided to put the GPS-GSM transmitter on the Rüppell's (which I nicknamed "Rupi").

We were now able to successfully track Rupi's movements. As it turned out, Rupi ended up following the wildebeest herds back to the Serengeti in Tanzania. Not only is this great data, but it also supports Munir's research on their large home ranges, proving that we need to protect these birds even outside of reserves like the Masai Mara.